How is value – both that which is valuable for human beings and that which has financial value – created by means of resources, work, and ideas? Human beings can decide to spend their energetic surplus according to their own choices. A human being is a homo creator who gives shape to his or her life by making conscious choices for themselves and for their community.

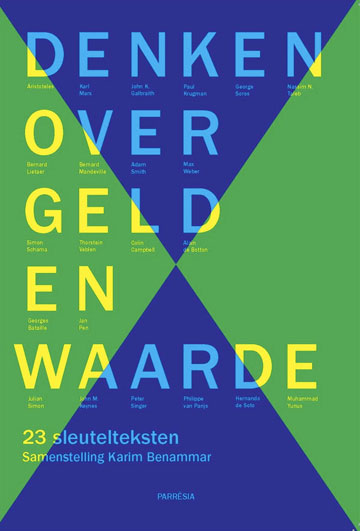

Thinking about Money and Value (published in Dutch; English introduction) I have selected 23 key texts of economists, philosophers, bankers and sociologists that give us insight into this question.

Read the Introductory chapter in English below by clicking Read more.

Introduction: the value of ideas

“The ideas of economists and political philosophers, both when they are right and when they are wrong, are more powerful than is commonly understood. Indeed the world is ruled by little else. Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influence, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist.”

So wrote John Maynard Keynes, an economist of no small reputation and influence himself. This book is a collection of such ideas that have to come to rule the world and practical men.

The current global economic infrastructure is enormous. It is solid, composed of high-rises and factories, ships and cars, oil and corn, and billions of consumer goods. It is also virtual: the price of oil varies according to the law of supply and demand, but also because of political and psychological considerations, and as a result of speculation. The logistic flows of world trade and the number of daily financial transactions boggle the mind. And yet, as the pieces in this book make clear, all this economic activity, material and virtual, ultimately rests on ideas and on human character traits such as trust, desire and the need to show off.

The global economy has not been well in recent years. The current Euro crisis has everyone in its grip, from nervous investors and politicians scrambling for answers to those whose very livelihood is at stake. This crisis comes on the heels of the severe banking crisis of 2008, in which losses on complex American mortgages vehicles destabilised the whole financial system. This led to drastic government measures such as the nationalisation of banks and automobile companies. Going back a little further in time, we remember the bursting of the Internet bubble in 2001, and the Asian, Russian and Mexican crises. Many of us try to make sense of what is happening today by deciphering economic news and opinions. While we all have plenty of day-to-day experience with money and are awash in economic information, few of us know how the economy really works.

Many economic texts present theories about reality, models, or different aspects of human nature. Part of economics consists in the elaboration of intriguing and grand ideas, which sometimes come to have an enormous impact. The main criterion I have used in making this selection is that every piece should present a novel perspective for thinking about money or wealth. Each of these texts fundamentally changed my mind about economics by adding a new perspective or by making me rethink my assumptions. As a philosopher, I am interested in the positions taken by these thinkers and the arguments they offer. I have selected the passages in the work in which these are most forcefully and clearly expressed. Sometimes this has meant focusing on a few key passages in the work; at other times compressing an essay or lecture to its argumentative backbone. The selections range from Antiquity to proposals for the future, and come from established economists and philosophers, from sociologists and historians, and also from bankers and traders.

The book is divided into three sections, each dealing with an aspect of economic thinking:

I. Money and investment: To understand how money functions, we must know something about banks and about how trust in currencies is established. Investing money leads to market valuations and periods of growth punctuated by recessions. There are bull markets, when the value of commodities, real estate and stock can soar, only to fall dramatically during a crisis.

II. Moral values in economic behaviour: In order to make sense of the need for savings and investment, we must understand the fundamental historical role of moral values such as thrift. Why did people decide to put their money away so that it could be invested? Why did they take pride in living simply and why were they suspicious of displays of wealth? The capitalist post-war economic system spawned a consumption boom, ushering in an age of affluence, a dramatic break with a much poorer past. What are the drivers of our consumption, what motivates our spending? We are also led to ponder the age-old question: can money make us happy?

III. The creation and sharing of wealth: Questions about our production and consumption system lead to us to wonder how economic growth occurs in the first place, and whether it is necessary. What are the causes of the economic affluence that we are experiencing now, and is it possible for these to be replicated worldwide? How should we share the wealth that is created? Is it possible for our economic behaviour to lead to the flourishing of all human lives?

I. Money and investment

Money: most of us use it every day, some of us are obsessed by it, while others insist that it cannot buy their love. Money is, at heart, a mystery: what is it exactly and what does it do? Where does it come from, and when it disappears, where does it go? How can value be created in the order of thousands of billions when times are good only to disappear when a recession strikes? Money is seen to have three main functions: it is a medium of exchange, it quantifies the value of goods, and it can be invested and accumulated.

- Money as a medium of exchange.

The Greek philosopher Aristotle described the exchange function of money in the fifth century B.C. as a third element which allows us to calculate the appropriate relationship between two goods. As such, it is nothing more than a useful mathematical shortcut to barter. Aristotle also makes a distinction between economics, which consists of running a household, and chremastike, the pursuit of money for its own sake. While he considers running a household properly to be an honourable activity, an interest in making money out of money is seen as a degenerate.

Once freed from its origins in barter, money begins to function as a universal exchange token. Money can be endlessly exchanged for everything else: it can buy anything. As Karl Marx stresses in his colourful contribution, in which he quotes Goethe and Shakespeare, money does not only enable us to buy all material goods, but also all the qualities associated with these goods. It can reverse our physical limitations, and buys respect, attention and even love. Money is so powerful that it turns everything into its opposite.

- Money as a unit of measurement.

Strange as it may seem, money itself does not need to have any intrinsic value. Almost anything can, and has, been used as money: shells, tobacco leaves, animal hides, and coffee are some of the more colourful examples. Precious metals, and in particular silver and gold, have played a more central role in giving value to money. They were used as direct equivalents, in that the weight of silver or gold contained in a coin was the measure of its value. In the end, however, it is the size of the economy and the flows of trade that dictate the value of currency. When Spain brought back ships full of silver from its South American mines in Potosi in the 17th century and flooded the European market with its newly minted wealth, it caused high rates of inflation and ultimately wrecked its own economy. Too much money chasing too few goods will cause prices to rise, and owning a lot of newly-discovered silver will not magically make you richer, since silver is ultimately a unit of measure and not a value in itself.

The amount of money in circulation (and the speed at which it circulates) is thus an important variable of the health of an economy and its possibility for sustained growth. This is illustrated in economist Paul Krugman’s story about the challenges faced by a baby-sitting co-op in making enough coupons for baby-sitting hours. Too few coupons lead to a decrease in baby-sitting activity: a recession. One fundamental cause of recessions is related to the difficulty of managing the money supply appropriately.

- Money as investment and accumulation.

Money can be used to invest in property and economic activity, and then value accumulates in hoards of gold or, more prosaically today, in titles, shares and bonds. Financial instruments make it possible for companies to be owned by a large group of anonymous investors, for government debt to be spread out across the globe, for pension funds to secure future revenues for their members, and for companies to hedge against currency swings. Stock exchange indexes function as an approximate barometer of the global hoard of wealth.

The accumulation of wealth, as everyone knows, has never been a smooth process, even discounting the effect of major upheavals such as wars and natural disasters. Stock exchanges move from boom to bust, going up and down in seemingly random fashion. While the function of money as a vehicle for investment and accumulation is thus a crucial component of our current system, it is impossible to predict or control. Complicated financial instruments such as derivatives or credit default swaps, coupled with lightning-fast computer trading and global interconnections, have created a system with no-one in charge. As explained in the contributions by the traders Nassim Taleb and George Soros, at times everyone, from workers to investors to governments, seems to be held hostage by the system.

- Money in the future.

Is this system no longer serves us, could it be changed? If we could rewrite the rules governing our financial system and change the role of money and investment, what could we do? Banker and thinker Bernard Lietaer makes some intriguing suggestions. First, we could bind the currency to the value of important resources, such as grain and oil. This will anchor value to the “real world” and decrease speculation and uncertainty.

A more radical proposal is replace the current system of interest on investment with a negative interest rate. We would all have to pay a small fee to keep our money valid, leading to its gradual depreciation rather than appreciation. Why is this important? The existence of positive interest automatically leads to a process of “discounting” the future: we value future returns at only a fraction of their worth because in future money will be worth less. This means that current returns take precedence over future returns, and causes short-term and unsustainable harvesting practices. By reversing interest, we can construct a system that values the future.

II. Moral values in economic behaviour

- Self-interest and economic growth

There has always an uneasy tension between spiritual values and worldly possessions. From Aristotle’s warnings about the unbridled pursuit of wealth to the Church’s prohibition on interest, the desire for financial gain was viewed with suspicion during much of history. From the Renaissance, however, perceptions began to change, and the new capitalist instinct received a moral boost from two sources. First, philosophers came up with the novel argument that individual self-interest would lead to a common good. Bernard Mandeville casts the desire and the pursuit of wealth as virtues in his fable about productive bees. Greed, ostentation, competition and debauchery reign, but the hive falls to pieces when honesty and self-control are imposed. Adam Smith argues that the common good is served if each focuses on their self-interest. Second, Protestantism made the accumulation of wealth, when undertaken with the right attitude, a virtue rather than a sin. The sociologist Max Weber uses Benjamin Franklin’s exhortations to frugality to claim that the new capitalist was a secular version of the pious merchant for whom the accumulation of wealth was a calling.

Self-interest as the engine for both personal enrichment and as a contribution to common wealth is elevated to the level of moral duty.

- Spending money: affluence, conspicuous consumption and consumerism

What do we do with the wealth we have accumulated? Money plays a crucial role in society, and our self-image in the developed world is to a large extent derived from our possessions. But do we consume only for practical reasons, or has consumer life taken on a new role in our society? Most of our current consumption is symbolic rather than driven by need. Can we ever overcome our need to consume? The historian Simon Schama shows how the newly affluent citizens of the Dutch Republic’s Golden Age struggled with the “embarrassment of riches”. They faced a difficult balancing act between enjoying and displaying their wealth on the one hand and a deep-seated suspicion about earthly pleasures and rewards on the other. The economist Thorstein Veblen coined the term “conspicuous consumption” at the end of the 19th century to describe the need to show off through possessions that emerged in the moneyed class. According to the sociologist Colin Campbell, though, modern consumerism is not fundamentally about the accumulation of goods, but about a deep-seated longing for an impossible ideal, which consumer objects temporarily satisfy.

- Money and happiness

Can wealth and possessions make us truly happy? Both those who affirm and those who deny this can be accused of being disingenuous. As Woody Allen famously said: “Money is better than poverty, if only for financial reasons”. Does the accumulation of wealth lead to happiness? Alain de Botton discovers that beyond a certain threshold, more money does not translate into more happiness. He uses the thinking of the philosopher Epicurus to show that the things that really matter in life, such as simple food, friendship, freedom and reflection, do not require a lot of money.

III. The creation and sharing of wealth

- Abundance

Where does wealth come from and how should it be shared? Since the beginning of civilisation, the surpluses produced by agriculture have been diverted to the development of craftsmanship, trade and industry, producing enough excess wealth for populations to flourish. While this growth has been pushed back by wars, famines and rapid population growth, the total wealth of humanity has kept on accruing. On average, we leave more wealth to future generations than we have inherited from our ancestors. Since the Renaissance and the Industrial Revolution we have enjoyed a steady progress in our level of wealth. The development of technology, coupled with the availability of energy sources and a growth-oriented economic system, has sped up this process of wealth creation. In our time, this has led to a vast democratization of wealth: the average citizen in the developed world today enjoys a life unattainable by the kings of bygone eras. The philosopher Georges Bataille describes the universe as an enormous system of surplus expenditure. The world is “sick with wealth”, and yet we find it difficult to translate this into affluence for everyone. The economist Julian Simon spent his life arguing that life keeps getting better and that the predictions of vast famines and the end of resources are not based on facts.

- Growth, surplus and excess

In an affluent society, we already produce far more than we need. The economic historian John Kenneth Galbraith shows that in order to keep the wheels of production turning, consumers must be convinced of the need to consume more through advertising. He sees managing the constant production of the surplus as the main economic challenge for our times. The economist Jan Pen shows that everyone wants economic growth, even those who claim that they have enough. John Maynard Keynes imagines a society in the future, in which the “economic problem” of satisfying our needs has been solved. He argues that we will have to learn how to live well when we no longer have the pressing need to focus primarily on making money.

- Sharing wealth

Despite our fundamental abundance and the creation of wealth over the past centuries, there are vast differences in income within societies as well as between societies. The distribution and sharing of wealth has always been a critical issue, leading to uprising and revolution, and lying at the heart of our political systems. Do we have an obligation to share our wealth, and if so, what is this obligation based on? The philosopher Peter Singer bases his reasoning on the “greatest good for the greatest number”. He uses an ingenious argument to show that as long as we can save lives for a few hundred dollars, we have an ethical duty to share as much of our income as we can. The economist Philippe Van Parijs takes a different approach. He is an avid promoter of the concept of a “basic income”, the notion that part of a society’s wealth should be distributed among its members without any preconditions.

There are also opportunities for the creation of wealth through the spread of global capitalism. The Peruvian economist Hernando De Soto argues that the mystery of capitalism lies not in a capitalist attitude to trade or in hard work, but rather in a legal system of property rights. When these are established and safeguarded, capitalism can thrive and people can flourish. The banker and Nobel Peace Prize winner Muhammad Yunus was one of the instigators of the concept of microcredit. The core innovation in lending to those who have no collateral lies in trusting women’s desire to improve their lives and their capacity to do so as a group. Yunus is now focusing on a second innovation, the idea of a “social business”, which has as its overriding mission to improve people’s lives and makes profit only to achieve this aim.

The perspectives presented in these selections function as different stepping-off points to think about the role of the economy and economics in our lives, about our attitude to money and finance, to economic growth and the distribution of wealth, and about new possibilities for the future. This compilation provides a great number of arguments from a lot of different perspectives. There is no consensus in interpretation; different economic theories explain the same reality through competing, and sometimes even contradictory theories. The system that we are all part of today works in practice, but is not so easily captured in one coherent theory. There are also great differences in the prescriptive aspect of economic ideas. How much money should be made available for the system to function optimally? What role should the State take in regulating trade and investment flows? How should wealth be distributed optimally from the perspective of justice or the perspective of economic growth? How much do we need and how comfortable will we be in enjoying our wealth?

May the ideas in these selections help trigger reflection on these topics and enable you to make your own mind up. I hope you will find out that the world of economic ideas is more complex, more nuanced and above all more exciting than you might have thought.